Northeast Japan was a prosperous region during the Jōmon era (14,000–300 BC), when hunting and gathering were the primary means of subsistence. Once rice cultivation became the norm, procuring food grew difficult due to severe cold and limited arable land. A man once described this land as a place to survive.

In Tōno, deities dwell in mountains, rivers, and even within the home. The presence of deities in one’s immediate surroundings was unquestioned, and prayer was woven into everyday life. Hunting in winter, planting in spring, spirits returning in summer, and harvesting rice in autumn. Throughout the year, people pray when they eat, die, mourn, and work. Without scientific knowledge, prayer was a crucial practice alongside wisdom inherited from ancestors, especially when survival meant confronting nature that lies beyond human comprehension. Whilst Buddhism and Shintoism have existed for centuries in Tōno and form a visible foundation, the unravelling of folk beliefs passed down and syncretised amongst people over many generations hints at a unique spiritual world and the stronghold of people’s hearts.

Prayer for mountains: Tōno is a small basin surrounded on all sides by mountains that possess a presence beyond human understanding. A place where souls return, a sacred site of spiritual power. Blessings such as game and wild vegetables are offered, whilst dangerous beasts like wolves and bears dwell there, often claiming human lives. Mountains have their own deity, sometimes appearing as a woman refusing entrance to other females, or taking the shape of red-faced, rugged men with an axe in hand. Just as people held varied impressions of mountains, the mountain deity visited in various forms. If you walk through Tōno, you will find stones inscribed with Yama-no-kami (mountain god) in many places.

Prayer for food: Will the year yield a bountiful harvest? This was the primary concern of farmers. During the celebration of the first full moon of the year, fortune-telling using rice cakes and walnuts took place, or pine trees were planted in snow-covered land as an imitation of rice planting, in the hope of a good harvest. With the belief that Ta-no-kami (rice field god) would come to inspect the newly planted rice fields, horses made of straw were prepared so the deity could return home. In today’s terms, it is akin to reserving a taxi for the gods.

Prayer for mourning: Lost souls watch over the living from a nearby mountain, returning to the living world each summer. During those few days, people spend time with their ancestors and the deceased. A tall lantern tree called Mukai-Toroge (greeting lantern tree) is placed in front of the house as a marker so that souls do not lose their way. Before the tombs, Haka Shishi, a form of Shishi Odori for mourning, is performed, and then a boat bearing fire is sent down the river, returning the souls to the otherworld. Ceremonies for the dead that are repeated annually serve as both a repose for souls and a reminder that you, too, will be commemorated one day after your passing. Sorrow and solace lie at the heart of prayers for mourning.

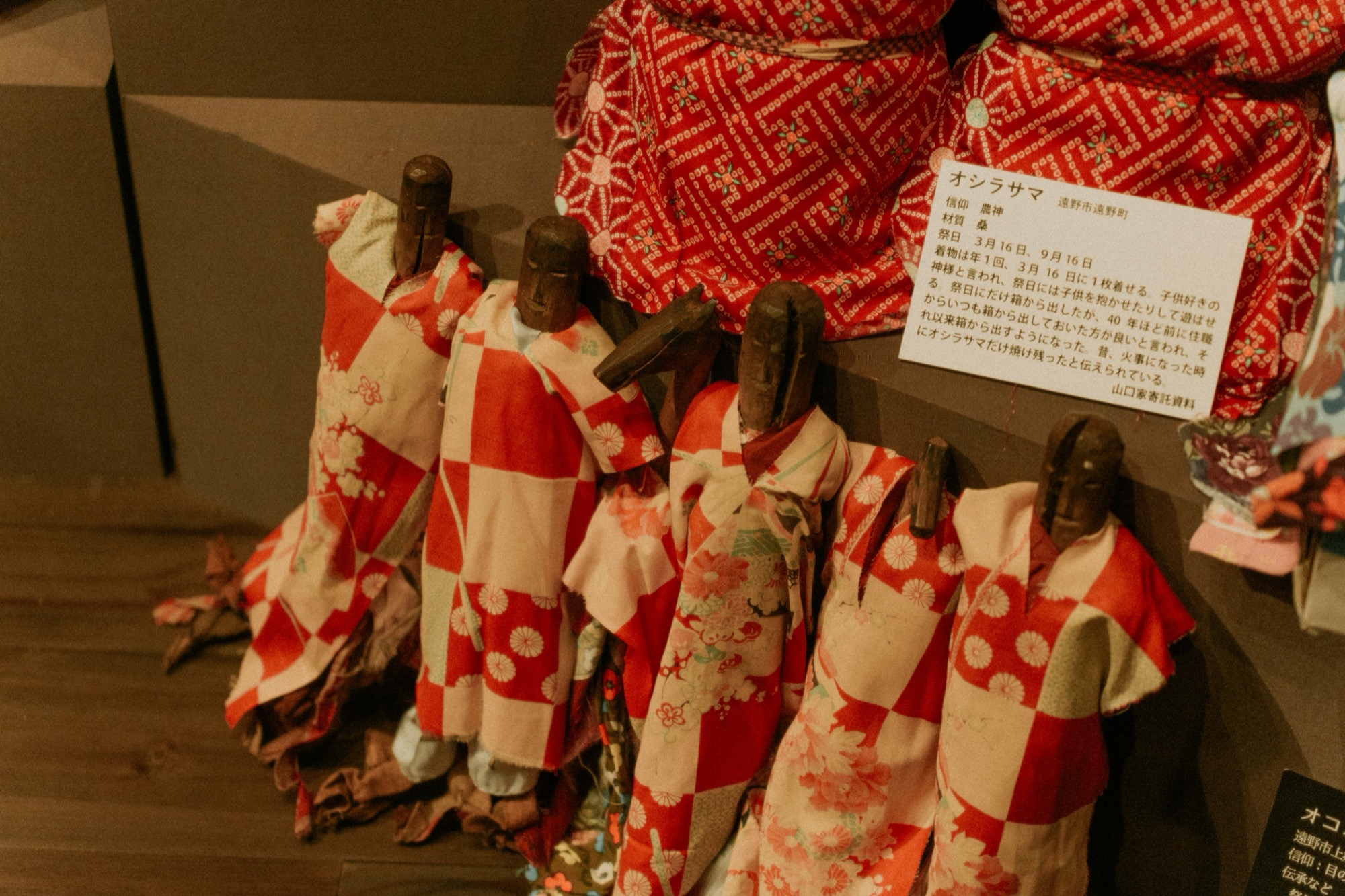

Prayer for livelihood: Tōno has another deity named Oshira-sama. They resemble wooden sticks wrapped in cloth, some existing for over 500 years. Oshira-sama is known as the deity of sericulture, the curing of eye diseases, and divination, as shamans employed them as ritual tools. In former times, fishermen would consult Oshira-sama for guidance on where to fish. In “The Legends of Tōno”, Oshira-sama is explained through a tragic love story between a horse and a girl; the origins of the tale are quite complex. Such complexity is the characteristic of folk beliefs, arising from local people’s struggles with life and the prayers offered to deities each time they faced hardship.

RCulture Bites

1Yama no kami (Mountain god)

A deity that dwells in and protects the mountain. Most famously, the myths tell of goddesses inhabiting the three mountains of Tōno. Those who made their living by entering the mountains – such as hunters, foresters, and ironworkers – held particularly devout beliefs. On December 12th, no one, including those working in the mountains, ventures into the mountain, as it is the day of Yama no kami, who is also a deity of fertility, said to give birth to twelve children at once.

RCulture Bites

2Oshira sama

A deity of folk worship seen throughout northeastern Japan, worshipped in Tōno for over 500 years. The form varies from a horse’s head to a woman’s face, male deity or female deity, and is said to govern sericulture, eyes, and divination. Oshira sama is usually kept in a box and then covered with a new cloth during a New Year event called Oshira Asobi. In Tōno, Oshira sama is often regarded as the household deity, and can still be found in 63 houses across the city (according to research conducted by Tōno City Museum in 2000). It appears in “The Legends of Tōno” as a tragic love story between a horse and a girl.

RCulture Bites

3Umakko Tsunagi (Tied horses)

An event in rural areas around Mount Kitakami to pray for a good harvest. Straw horses are offered at water sources in rice fields, wells, and road junctions in the hope that there will be more grain than the horses can carry and no shortage of water. It is said that the rice field deity rides on the straw horse to inspect the crops.

RCulture Bites

4Mukai-Toroge (Greeting Lantern Tree)

A tradition passed down in Tōno. Every year for three years following a death, a lantern tree is placed in front of the house as a landmark for ancestors returning home from August 7th until the end of August.

RSite

1Tōno Hachiman Shrine

An ancient shrine known to have been built by the Asonuma clan, who were granted the land of Tōno for their role in defeating the Ōshū Fujiwara clan in 1189. At the Tōno Festival in September, Tōno Southern Yabusame (mounted archery), which originated in 1335, is held in a vast 450-metre field, whilst around forty local performing arts groups gather to perform Kagura, Shishi Odori, Nambu Hayashi (songs), and Sansa dance. A cat shrine has been built in recent years, and cat enthusiasts from across Japan continue to visit.

RSite

2Gohyaku Rakan (Statues of Five Hundred Disciples of Buddha)

This is a sacred space where several hundred Buddhist figures are carved into rocks. Following the devastating famine of the 1750s, a Buddhist priest carved them to provide rest for the souls of those who died unattended. It is a place to learn about the severity of survival in Tōno and to appreciate the beauty of the landscape. You should reach it by walking along the forest paths in front of Atago Shrine.

RSite

3Denshō-en (Garden of Tradition)

A cultural tourism facility near the Kappa pond, a place where mythical creatures appear from the water. The garden showcases the Nambu Magariya house (designated as a nationally important cultural property), the memorial hall of Kizen Sasaki, who was the storyteller of “The Legends of Tōno”, whilst also exhibiting Zashiki Warashi (parlour child), Oshira sama, and lifestyles from the era when the tales were born.

RSite

4Tōno City Museum

The first museum in Japan dedicated to folklore studies. Visitors can learn about “The Legends of Tōno”, beliefs and lifestyles, hunting, and Shugendō (a body of practices that evolved during the seventh century, drawn from local folk-religious practices, Shinto mountain worship, and Buddhism).